| - People - |

Minorities

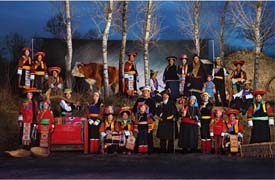

The Chinese population of more than one billion consists of a great many ethnic national minorities. These ethnic groups are as diverse as they are unique; each one contributing its own drop in the river of Chinese culture and history. Of the countless hundreds of minorities within the greater China region, these are the 56 most populous.

This page contains Chinese characters. Please see here for information regarding how to read Chinese on your computer.

Contents

SEE Also:

Achang (Chinese: 阿昌族; Pinyin: Āchāng Zú)

More than 90 percent of the 27,700 Achangs live in Longchuan, Lianghe and Luxi counties in the Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture in southwestern Yunnan Province. The rest live in Longling County in the neighboring Baoshan Prefecture.

These areas are on the southern tip of the Gaoligong Mountains. The climate is warm; the land fertile, crisscrossed by the Daying and Longchuan rivers and their numerous tributaries. The river valleys contain many plains, the Fusa and Lasa being the largest of them. Dense forests populated by deer, musk deer and bears cover the mountain slopes. Natural resources, such as coal, iron, copper, lead, mica and graphite, abound.

Achangs speak a language belonging to the Tibetan-Myanmese language family of the Chinese-Tibetan system. Most Achangs also can speak Chinese and the language of Dais. Their written language is Chinese.

Bai (Chinese: 白族; Pinyin: Bái Zú)

Of the 1,598,100 Bai people, 80 per cent live in concentrated communities in the Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province, southwest China. The rest are scattered in Xichang and Bijie in neighboring Sichuan and Guizhou provinces respectively.

The Bais speak a language related to the Yi branch of the Tibetan-Myanmese roup of the Chinese-Tibetan language family. The language contains a large number of Chinese words due to the Bais' long contact with the majority Chinese ethnic group--Han.

Situated on the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, the Bai area is crisscrossed with rivers, of which the major ones are the Lancang, the Nujiang and the Jinsha. The river valleys, dense forests and vast tracts of land form a beautiful landscape and provide an abundance of crops and fruits. The area round Lake Erhai in the autonomous prefecture is blessed with a mild climate and fertile land yielding two crops a year. Here, the main crops are rice, winter wheat, beans, millet, cotton, rape, sugar-cane and tobacco. The forests have valuable stocks of timber, herbs of medicinal value and rare animals. Mt. Diancang by Lake Erhai contains a rich deposit of the famous Yunnan marble, which is basically pure white with veins of red, light blue, green and milky yellow. It is treasured as building material as well as for carving.

Blang (Chinese: 布朗族; Pinyin: Bùlǎng Zú)

The Blang people, numbering 82,400, live mainly in Mt. Blang, Xiding and Bada areas of Menghai County in the Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture in southwestern Yunnan Province. There are also scattered Blang communities in the neighboring Lincang and Simao prefectures. All the Blangs inhabit mountainous areas 1,500-2,000 meters above sea level. The Blangs in Xishuangbanna have always lived harmoniously with their neighbors of both the other minority nationalities and the majority Han.

The Blang people inhabit an area with a warm climate, plentiful rainfall, fertile soil and rich natural resources. The main cash crops are cotton, sugar-cane and the world famous Pu'er tea. In the dense virgin forests grow various valuable trees, and valued medicinal herbs such as pseudoginseng, rauwolfia verticillata (used for lowering high blood pressure) and lemongrass, from which a high-grade fragrance can be extracted. The area abounds in copper, iron, sulfur and rock crystal.

The Blangs speak a language belonging to the South Asian language family. The language does not have a written form, but Blangs often know the Dai, Va and Han languages.

According to historical records, an ancient tribe called the "Pu" were the earliest inhabitants of the Lancang and Nujiang river valleys. These people may have been the ancestors of today's Blangs.

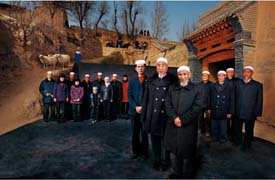

Bonan (Chinese: 保安族; Pinyin: Bǎoān Zú)

The Bonan is one of China's smallest ethnic minorities, with only 11,700 people. Its language belongs to the Mongolian branch of the Altaic language family and is close to that of the Tu and Dongxiang ethnic minorities. Due to long years of contacts and exchanges with the neighboring Han and Hui people, the Bonan people have borrowed quite a number of words from the Han language. The Han language is accepted as the common written language among the Bonans.

Judging from their legends, language features and customs, many of which were identical with those of the Mongolians, the Bonan minority seems to have taken shape after many years of interchanges during the Yuan and Ming (1271- 1644) periods between Islamic Mongolians who settled down as garrison troops in Qinghai's Tongren County, and the neighboring Hui, Han, Tibetan and Tu people. The Bonans used to live in three major villages in the Baoan region, situated along the banks of the Longwu River within the boundaries of Tongren County.

During the early years of the reign of Qing Emperor Tongzhi (1862- 1874), they fled from the oppression of the feudal serf owners of the local Lamaist Longwu Monastery. After staying for a few years in Xunhua, they moved on into Gansu Province and finally settled down at the foot of Jishi Mountain in Dahejia and Liuji, Linxia County. Incidentally, they again formed themselves into three villages -- Dadun, Ganmei and Gaoli -- which they referred to as the "tripartite village of Baoan" in remembrance of their roots.

Buyei (Chinese: 布依族; Pinyin: Bùyī Zú)

Most of China's 2,548,300 Bouyei people live in several Bouyei-Miao autonomous counties in Xingyi and Anshun prefectures and Qiannan Bouyei-Miao Autonomous Prefecture in Guizhou Province. Others are distributed in counties in the Qiandongnan Miao-Dong Autonomous Prefecture or near Guiyang, the capital of Guizhou.

The Bouyei region is on the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, which slopes from an altitude of 1,000 meters in the north to 400 meters in the south. The Miaoling Mountains stretch across the plateau, forming part of its striking landscape.

The famous Huangguoshu Falls cascade down more than 60 meters near the Yunnan-Guizhou highway in Zhenning Bouyei-Miao Autonomous County. The thunder of water can be heard several kilometers away, and mists from the falls contribute to a magnificent view.

The Bouyeis are blessed with fertile land and a mild climate. The average annual temperature is 16 degrees Centigrade, and an essentially tropical environment, receiving between 100 and 140 centimeters of rain a year, is ideal for farming. Local crops include paddy rice, wheat, maize, dry rice, millet, sorghum, buckwheat, potatoes and beans. Farmers also grow cotton, ramie, tobacco, sugar cane, tung oil, tea and oil-tea camellia as profitable cash crops.

As the Red River valley is low-lying and tropical, paddy rice yields two harvests annually. Silk, hemp, bamboo shoots and bananas complement the local economy, and coffee and cocoa have also been planted there recently.

Dai (Chinese: 傣族; Pinyin: Dǎi Zú)

Also called Dai Lue, one of the Tai ethnic groups, the Dai ethnic group lives in the southern part of Yunnan Province, mainly in the Xishuangbanna region. The area is subtropical, with plentiful rainfall and fertile land.

Local products include rice, sugar cane, coffee, hemp, rubber, camphor and a wide variety of fruits. Xishuangbanna is the home of China's famous Pu'er tea. The dense forests produce large amounts of teak, sandalwood and medicinal plants, and are home to wild animals including elephants, tigers and peacocks.

The Dai language belongs to the Chinese-Tibetan language family and has three major dialects. It is written in an alphabetic script.

Daur (Chinese: 达斡尔族; Pinyin: Dáwòěr Zú)

The Daurs live mainly in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Heilongjiang Province. About several thousand of them are found in the Tacheng area in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwest China. They are descendents of Daurs who moved to China's western region in the early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The Daurs speak a language related to Mongolian and used Manchu during the Qing Dynasty as their written language. Since the 1911 Revolution, mandarin Chinese has replaced Manchu.

The biggest Daur community is in the Morin Dawa Daur Autonomous Banner, which was set up on August 15, 1958 on the left bank of the Nenjiang River in Heilongjiang Province. This 11,943 sq. km.-area has lush pasture and farmland. The main crops are maize, sorghum, wheat, soybeans and rice. In the mountains which border the Daur community on the north are stands of valuable timber, such as oak, birch and elm and medicinal herbs. Wildlife, including bears, deer, lynx and otters are found in the forests. Mineral deposits in the area include gold, mica, iron and coal.

De'ang (Chinese: 德昂族; Pinyin: Déáng Zú)

The number of De'ang people in China totals 15,500. Small as their population is, the people of this ethnic group are quite widely distributed over Yunnan Province. Most of them dwell in Santai Township in Luxi County of the Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture and in Junnong Township in Zhenkang County of the Lincang Prefecture. The others live scattered in Yingjiang, Ruili, Longchuan, Baoshan, Lianghe and Gengma counties. Some De'angs live together with the Jingpo, Han, Lisu and Va nationalities in the mountainous areas. And a small number of them have their homes in villages on flatland peopled by the Dais The De'ang language belongs to the South Asian family of languages. The De'angs have no written script of their own, and many of them have learned to speak the Dai, Han or Jingpo languages, and some can read and write in the Dai language. An increasing number of them have picked up the Han language in years after the mid-20th century.

Derung (Chinese: 独龙族; Pinyin: Dúlóng Zú)

The Derungs, numbering about 4,700, live mainly in the Dulong River valley of the Gongshan Drung and Nu Autonomous County in northwestern Yunnan Province. Their language belongs to the Tibetan-Myanmese group of the Chinese-Tibetan language family. Similar to the language of the Nu people, their neighbors, it does not have a written form and, traditionally, records were made and messages transmitted by engraving notches in wood and tying knots.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the places where the Drungs lived were under the jurisdiction of the Nanzhao and Dali principalities. From the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) to the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the Drungs were ruled by court-appointed Naxi headmen. In modern times, the ethnic minority distinguished itself by repulsing a British military expedition in 1913.

Dong (Chinese: 侗族; Pinyin: Dòng Zú)

Nestling among the tree-clad hills dotting an extensive stretch of territory on the Hunan-Guizhou-Guangxi borders are innumerable villages in which dwell the Dong people.

The population of this ethnic group in China is 2.5 million. Situated no more than 300 km north of the Tropic of Cancer, the area peopled by the Dongs has a mild climate and an annual rainfall of 1,200 mm. The Dong people grow enormous numbers of timber trees which are logged and sent to markets. Tong-oil and lacquer and oil-tea camellia trees are also grown for their edible oil and varnish.

The most favorite tree of the people of this ethnic group is fir, which is grown very extensively. Whenever a child is born, the parents begin to plant some fir saplings for their baby. When the child reaches the age of 18 and marries, the fir trees, that have matured too, are felled and used to build houses for the bride and groom. For this reason, such fir trees are called "18-year-trees." With the introduction of scientific cultivation methods, a fir sapling can now mature in only eight or 10 years, but the term "18-year-trees" is still current among the Dong people.

Farming is another major occupation of the Dongs, who grow rice, wheat, millet, maize and sweet potatoes. Their most important cash crops are cotton, tobacco, rape and soybean.

With no written script of their own before 1949, many Dongs learned to read and write in Chinese. Philologists sent by the central government helped work out a Dong written language on the basis of Latin alphabet in 1958.

Dongxiang (Chinese: 东乡族; Pinyin: Dōngxiāng Zú)

People of the Dongxiang ethnic minority live in the part of the Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture situated south of the Yellow River and southwest of Lanzhou, capital city of the northwest province of Gansu. Half of them dwell in the Dongxiang Autonomous County, and the rest are scattered in Hezheng and Linxia counties, the city of Lanzhou, the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and some other places.

The Dongxiang ethnic minority received its name from the place it lives -- Dongxiang. However, this ethnic group was not recognized as a minority prior to the founding of the People's Republic in 1949. The Dongxiangs were then called "Dongxiang Huis" or "Mongolian Huis." The Dongxiang language is basically similar to Mongolian, both belonging to the Mongolian branch of the Altaic language family. It contains quite a number of words borrowed from the Han Chinese language. Most of the Dongxiang people also speak Chinese, which is accepted as their common written language. Quite a few of them can use the Arabic alphabet to spell out and write Dongxiang or Chinese words.

The Dongxiangs are an agricultural people who grow potatoes, wheat, maize and broad beans as well as hemp, rapeseed and other industrial crops.

Ewenki (Chinese: 鄂温克族; Pinyin: Èwēnkè Zú)

This ethnic minority is distributed across seven banners (counties) in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and in Nahe County of Heilongjiang Province, where they live together with Mongolians, Daurs, Hans and Oroqens.

The Ewenki people have no written script but a spoken language composed of three dialects belonging to the Manchu-Tungusic group of the Altai language family. Mongolian is spoken in the pastoral areas while the Han language is used in agricultural regions. The Ewenki Autonomous Banner, nestled in the ranges of the Greater Hinggan Mountains, is where the Ewenkis live in compact communities. A total of 19,110 square kilometers in area, it is studded with more than 600 small and big lakes and 11 springs. The pastureland here totaling 9,200 square kilometers is watered by the Yimin and four other rivers, all rising in the Greater Hinggan Mountains.

Nantunzhen, the seat of the banner government, is a rising city on the grassland. A communication hub, it is the political, economic and cultural center of the Ewenki Autonomous Banner.

Large numbers of livestock and great quantities of knitting wool, milk, wool-tops and casings are produced in the banner. Some 20-odd of these products are exported. The yellow oxen bred on the grassland have won a name for themselves in Southeast Asian countries. Pelts of a score or so of fur-bearing animals are also produced locally.

Reeds are in riot growth and in great abundance along the Huihe River in the banner. Some 35,000 tons are used annually for making paper. Lying beneath the grassland are rich deposits of coal, iron, gold, copper and rock crystal.

Gaoshan (Chinese: 高山族; Pinyin: Gāoshān Zú)

The Gaoshan people, about 300,000 in total, live mainly in Taiwan. They account for less than 2 per cent of the 17 million inhabitants, based on statistics published by Taiwan authorities in June 1982. The majority of them live in mountain areas and the flat valleys running along the east coast of Taiwan Island, and on the Isle of Lanyu. About 1,500 live in such major cities as Shanghai, Beijing and Wuhan and in Fujian Province on the mainland.

The Gaoshans do not have their own script, and their spoken language belongs to the Indonesian group of the Malay/Polynesian language family.

Taiwan Island, home to the Gaoshans, is subtropical in climate with abundant precipitation and fertile land yielding two rice crops a year (three in the far south). Being one of China's major sugar producers, Taiwan also grows some 80 kinds of fruit, including banana, pineapple, papaya, coconut, orange, tangerine, longan and areca. Taiwan's oolong and black teas are among its most popular items for export.

The Taiwan Mountain Range runs from north to south through the eastern part of the island, which is 55 per cent forested. Over 70 per cent of the world's camphor comes from Taiwan. Short and rapid rivers flowing from the mountains provide abundant hydropower, and the island is blessed with rich reserves of gold, silver, copper, coal, oil, natural gas and sulfur. Salt is a major product of the southeast coast, and the offshore waters are ideal fishing grounds.

The Gaoshans are mainly farmers growing rice, millet, taro and sweet potatoes. Those who live in mixed communities with Han people on the plains work the land in much the same way as their Han neighbors. For those in the mountains, hunting is more important, while fishing is essential to those living along the coast and on small islands.

Gaoshan traditions make women responsible for ploughing, transplanting, harvesting, spinning, weaving, and raising livestock and poultry. Men's duties include land reclamation, construction of irrigation ditches, hunting, lumbering and building houses.

Flatland inhabitants entered feudal society at about the same time as their Han neighbors. Private land ownership, land rental, hired labor and the division between landlords and peasants had long emerged among these Gaoshans. But, in Bunong and Taiya, land was owned by primitive village communes. Farm tools, cattle, houses and small plots of paddy field were privately owned. A primitive cooperative structure operated in farming and the bag of collective hunting was distributed equally among the hunters with an extra share each to the shooter and the owner of the hound that helped.

Twenty-nine hundred Gaoshans now live on the mainland. Though small in number, these Gaoshans have their deputies to the National People's Congress, China's supreme organ of power.

Gelao (Chinese: 仡佬族; Pinyin: Gēlǎo Zú)

The 438,200 Gelos live in dispersed clusters of communities in about 20 counties in western Guizhou Province, four counties of the Wenshan Zhuang-Miao Autonomous Prefecture in southeastern Yunnan Province and the Longlin Multi-ethnic Autonomous County in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

Only about a quarter of the Gelos still speak the Gelo language belonging to the Chinese-Tibetan language family. Yet, because of close contact with other ethnic groups, their language has not remained pure -- even within counties. There are Gelo-speaking people unable to converse with each other. For this reason, the language of the Hans, or Chinese, has become their common language, though many Gelos have learned three or four languages from other people in their communities, including the Miaos, Yis and Bouyeis. Living among other ethnic groups, the Gelos have become largely assimilated to the majority Han customs.

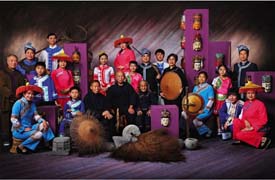

Han (Chinese: 汉族; Pinyin: Hàn Zú)

The Han are the majority ethnic group within China and the largest single human ethnic group in the world. The Han Chinese constitute about 92 percent of the population of mainland China and about 19 percent of the entire global human population. The name was occasionally translated as the "Chinese proper" in older texts (pre-1980s) and is commonly rendered in Western media as the "ethnic Chinese."

The term "Han Chinese" is used to distinguish the majority from the various minorities in and around China. The name comes from the Han Dynasty which succeeded the short-lived Qin Dynasty that reunited China. The Zhou dynasty, which preceded the Qin, was a period of consolidation when the various tribes coalesced into Warring States, which then annexed each other. It was during the Qin Dynasty and the Han Dynasty that the various tribes of China began to feel that they belonged to the same ethnic group, compared with "barbarians" around them. In addition, the Han Dynasty is considered a high point in Chinese civilization, able to project its power far into Central Asia.

Even today many Chinese people call themselves "Han persons" (Hànrén). The term Han Chinese is sometimes used synonymously with "Chinese" without regard to the 55 other minority Chinese ethnic groups; usage of this kind tends to be frowned upon by Chinese nationals, who regard the phrase Zhongguó rén (中國人) to be a more precise terminology.

Amongst Southern Chinese, a different term exists within various languages like Cantonese, Hakka and Minnan, but which means essentially the same thing. The term is Tángrén (唐人, literally "the people of Tang"). This also derives from another Chinese dynasty, the Tang dynasty, which is regarded as another zenith of Chinese civilization. In fact, the term survives in most Chinese references to Chinatown, known as 唐人街 ("Street of Tang People").

In Southeast Asia, another term used commonly by overseas Chinese is Huaren (Simplified Chinese: 华人; Traditional Chinese: 華人; Hanyu Pinyin: huárén), derived from Zhonghua (中华), a literary name for China. The usual translation is "ethnic Chinese". Sometimes the term is restricted to refer to only those Chinese who are overseas (outside Greater China).

Hani (Chinese: 哈尼族; Pinyin: Hāní Zú)

Most of the 1,254,800 Hanis live in the valleys between the Yuanjiang and Lancang rivers, that is, the vast area between the Ailao and Mengle mountains in southern Yunnan Province. They are under the jurisdiction of the Honghe Hani-Yi Autonomous Prefecture, which includes Honghe, Yuanyang, Luchun and Jinping counties. Others dwell in Mojiang, Jiangcheng, Pu'er, Lancang and Zhenyuan counties in Simao Prefecture; in Xishuangbanna's Menghai, Jinghong and Mengla counties; in Yuanjiang and Xinping, Yuxi Prefecture, and (a small number) in Eshan, Jianshui, Jingdong and Jinggu counties.

Their language belongs to the Yi branch of the Tibetan-Myanmese language group of the Chinese-Tibetan language family. Having no script of their own before 1949, they kept records by carving notches on sticks. In 1957 the people's government helped them to create a script based on the Roman alphabet.

The areas inhabited by the Hanis have rich natural resources. Beneath the ground are deposits of tin, copper, iron, nickel and other minerals. Growing on the rolling Ailao Mountains are pine, cypress, palm, tung oil and camphor trees, and the forests abound in animals such as tigers, leopards, bears, monkeys, peacocks, parrots and pheasants. Being subtropical, the land is fertile and the rainfall plentiful -- ideal for growing rice, millet, cotton, peanuts, indigo and tea. Xishuangbanna's Nanru Hills are one of the country's major producers of the famous Pu'er tea.

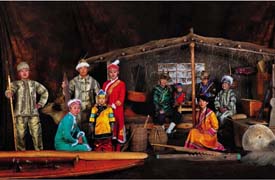

Hezhe (Chinese: 赫哲族; Pinyin: Hèzhé Zú)

The Hezhes are one of the smallest ethnic minority groups in China. In fact, poverty and oppression had reduced their numbers to a mere 300 at the time of the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949. Since then, however, they have made speedy advances in their economic life and health care, so that by 1990 the population had grown to 4,300.

They are a nomadic people who live mainly by hunting and fishing in the plain formed by the Heilong, Songhua and Wusuli rivers in Tongjiang, Fuyuan and Raohe counties in northeast China's Heilongjiang Province. Their language, which belongs to the Manchu-Tungusic group of the Altaic family, has no written form. For communication with outsiders they use the spoken and written Chinese language.

In winter they travel by sled and hunt on skis. They are also skilled at carpentry, tanning and iron smelting; but these are still cottage industries.

Traditional Hezhe clothing is made of fish skins and deer hides. The decorations of the clothes consist of buttons made of catfish bones and collars and cuffs dyed in cloud-shaped patterns. Women wear fish-skin and deer-hide dresses decorated with shells and colored strips of dyed deer hide in cloud, plant and animal designs. Bear skins and birch bark are also used to make thick boots which everyone wears in winter.

Hui (Chinese: 回族; Pinyin: Huí Zú)

With a sizable population of 8.61 million, the Hui ethnic group is one of China's largest ethnic minorities. People of Hui origin can be found in most of the counties and cities throughout the country, especially in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Gansu, Qinghai, Henan, Hebei, Shandong and Yunnan provinces and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region.

The name Hui is an abbreviation for "Huihui," which first appeared in the literature of the Northern Song Dynasty (960- 1127). It referred to the Huihe people (the Ouigurs) who lived in Anxi in the present-day Xinjiang and its vicinity since the Tang Dynasty (618- 907). They were actually forerunners of the present-day Uygurs, who are totally different from today's Huis or Huihuis.

During the early years of the 13th century when Mongolian troops were making their western expeditions, group after group of Islamic-oriented people from Middle Asia, as well as Persians and Arabs, either were forced to move or voluntarily migrated into China. As artisans, tradesmen, scholars, officials and religious leaders, they spread to many parts of the country and settled down mainly to livestock breeding. These people, who were also called Huis or Huihuis because their religious beliefs were identical with people in Anxi, were part of the ancestors to today's Huis.

Earlier, about the middle of the 7th century, Islamic Arabs and Persians came to China to trade and later some became permanent residents of such cities as Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Hangzhou, Yangzhou and Chang'an (today's Xi'an). These people, referred to as "fanke" (guests from outlying regions), built mosques and public cemeteries for themselves. Some married and had children who came to be known as "tusheng fanke," meaning "native-born guests from outlying regions." During the Yuan Dynasty (1271- 1368), these people became part of the Huihuis, who were coming in great numbers to China from Middle Asia.

The Huihuis of today are therefore an ethnic group that finds its origins mainly with the above-mentioned two categories, which in the course of development took in people from a number of other ethnic groups including the Hans, Mongolians and Uygurs.

It is generally acknowledged that Huihui culture began mainly during the Yuan Dynasty.

Jing (Chinese: 景族; Pinyin: Jǐng Zú)

The 18,700 people of this very small ethnic minority live in compact communities primarily in the three islands of Wanwei, Wutou and Shanxin in the Fangcheng Multi-ethnic Autonomous County, the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, near the Sino-Vietnamese border. About one quarter of them live among the Han and Zhuang ethnic groups in nearby counties and towns.

The Jings live in a subtropical area with plenty of rainfall and rich mineral resources. The Beibu Gulf to its south is an ideal fishing ground. Of the more than 700 species of fish found there, over 200 are of great economic value and high yields. Pearls, sea horses and sea otters which grow in abundance are prized for their medicinal value. Seawater from the Beibu Gulf is good for salt making. The main crops there are rice, sweet potato, peanut, taro and millet, and sub-tropical fruits like papaya, banana and longan are also plentiful. Mineral deposits include iron, monazite, titanium, magnetite and silica. The large tracts of mangroves growing in marshy land along the coast are a rich source of tannin, an essential raw material for the tanning industry.

The Jing people had their own script which was called Zinan. Created on the basis of the script of the Han people towards the end of the 13th century, it was found in old song books and religious scriptures. Most Jings read and write in the Han script because they have lived with Hans for a long time. They speak the Cantonese dialect.

The ancestors of the Jings emigrated from Viet Nam to China in the early 16th century and first settled on the three uninhabited lands since the neighborhood had been populated by people of Han and Zhuang ethnic group. Shoulder to shoulder with the Hans and Zhuangs there, they developed the border areas together and sealed close relations in their joint endeavors over the centuries.

Jingpo (Chinese: 景颇族; Pinyin: Jǐngpō Zú)

The Jingpos, numbering 119,300, live mostly in the Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province, together with the De'ang, Lisu, Achang and Han peoples. A few of them are found in the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture.

The Jingpos mainly inhabit tree-covered mountainous areas some 1,500 meters above sea level, where the climate is warm. Countless snaking mountain paths connect Jingpo villages, which usually consist of two-story bamboo houses hidden in dense forests and bamboo groves.

The area abounds in rare woods and medicinal herbs. Among cash crops are rubber, tung oil, tea, coffee, shellac and silk cotton. The area's main mineral resources are iron, copper, lead, coal, gold, silver and precious stones. Tigers, leopards, bears, pythons, pheasants and parrots live in the region's forests.

The Jingpos speak a language belonging to the Tibetan-Myanmese family of the Chinese-Tibetan language system. Until 70 years ago, when an alphabetic system of writing based on Latin letters was introduced, the Jingpos kept records by notching wood or tying knots. Calculation was done by counting beans. The new system of writing was not widely used, however. After 1949, with the help of the government, the Jingpo people have started publishing newspapers, periodicals and books in their own language.

According to local legends and historical records, Jingpo ancestors in ancient times inhabited the southern part of the Xikang-Tibetan Plateau. They gradually migrated south to the northwestern part of Yunnan, west of the Nujiang River. The local people, together with the newly-arrived Jingpos, were called "Xunchuanman," who lived mainly on hunting.

During the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), the imperial court set up a provincial administrative office in Yunnan, which had the Xunchuan area under its jurisdiction. As production developed, various Jingpo groups gradually merged into two big tribal alliances -- Chashan and Lima. They were headed by hereditary nobles called "shanguan." Freemen and slaves formed another two classes. Deprived of any personal freedom, the slaves bore the surname of their masters and did forced labor.

During the early 15th century, the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), which instituted a system of appointing local hereditary headmen in national minority areas, set up two area administrative offices and appointed Jingpo nobles as administrators. In the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the area inhabited by Jingpos was under the jurisdiction of prefectural and county offices set up by the Qing court.

Beginning from the 16th century, large numbers of Jingpo people moved to the Dehong area. Under the influence of the Hans and Dais, who had advanced production skills and practiced a feudal economy, Jingpos began to use iron tools including the plough, and later learned to grow rice in paddy fields. This learning process was accompanied by raised productivity and a transition toward feudalism. Slaves revolted or ran away. All these factors brought the slave system to a quick end in the middle of last century.

Jino (Chinese: 基诺族; Pinyin: Jīnuò Zú)

Numbering 18,000 in all, the Jinos live in the Jinoluoke Township of Jinghong County in the Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province.

The language of this ethnic minority belongs to the Tibetan-Myanmese group of the Chinese-Tibetan language family. Its structure and vocabulary have much in common with Yi and Myanmese. Without a written language of their own, the Jino people used to keep records by notching on wood or bamboo.

Jinoluoke is a mountainous area stretching for 70 kilometers from east to west and 50 kilometers from north to south. The climate there is rainy and subtropical with an average annual temperature of 18 to 20 degrees. The rainy season lasts from May to September with July and August having the heaviest rainfall. The rest of the year is dry.

Jino land is crisscrossed by numerous rivers and streams, the longest being the Pani and the Small Black rivers. The major crops are upland and wet rice and corn. The famous Pu'er tea grows on Mount Jino. Jinoluoke also has a long history of cotton-growing and is abundant in such tropical fruits as bananas and papayas. Elephants and wild oxen roam the dense primeval forests which are also the habitat of monkeys, hornbills and other birds. Jinoluoke is also rich in mineral resources.

It is said that the Jinos migrated to Jinoluoke from Pu'er and Mojiang or places even farther north. It seems likely that they still lived in a matriarchal society when they first settled around the Jino Mountain. Legend has it that the first settler on the mountain ridge was a widow by the name of Jiezhuo. She gave birth to seven boys and seven girls who later married each other. As the population grew, the big family was divided into two groups to live in as many villages, or rather two clans that could intermarry. One was called Citong, the patriarchal village, and the other was Manfeng, the matriarchal village. With the passage of time, the Jino population multiplied and more Jino villages came into existence.

Kazak (Chinese: 哈萨克族; Pinyin: Hāsàkè Zú)

The Kazak ethnic minority, with a population of over a million, mainly lives in the Ili Kazak Autonomous Prefecture, Mori Kazak Autonomous County and Barkol Kazak Autonomous County in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Some are also located in the Haixi Mongolian, Tibetan and Kazak Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai Province and the Aksay Kazak Autonomous County in Gansu Province.

The Kazak language belongs to the Turkic branch of the Altaic language family. As the Kazaks live in mixed communities with the Hans, Uygurs and Mongolians, the Kazaks have assimilated many words from these languages. They had a written language based on the Arabic alphabet, which is still in use, but a new Latinized written form was evolved after the founding of the Peoplel's Republic of China.

Except for a few settled farmers, most of the Kazaks live by animal husbandry. They migrate to look for pasturage as the seasons change. In spring, summer and autumn, they live in collapsible round yurts and in winter build flat-roofed earthen huts in the pastures. In the yurt, living and storage spaces are separated. The yurt door usually opens to the east, the two flanks are for sleeping berths and the center is for storing goods and saddles; in front are placed cushions for visitors. Riding and hunting gear, cooking utensils, provisions and baby animals are kept on both sides of the door.

The pastoral Kazaks live off their animals. They produce a great variety of dairy products. For instance, Nai Ge Da (milk dough) Nai Pi Zi (milk skin) and cheese. Butter is made from cow's and sheep's milk. They usually eat mutton stewed in water without salt--a kind of meat eaten with the hands. By custom, they slaughter animals in late autumn and cure the meat by smoking it for the winter. In spring and summer, when the animals are putting on weight and producing lots of milk, the Kazak herdsmen put fresh horse milk in shaba (barrels made of horse hide) and mix it regularly until it ferments into the cloudy, sour horse milk wine, a favorite summer beverage for the local people. The richer herdsmen drink tea boiled with cow's or camel's milk, salt and butter. Rice and wheat flour confections also come in a great variety: Nang (baked cake), rice cooked with minced mutton and eaten with the hands, dough fried in sheep's fat, and flour sheets cooked with mutton. Their diet contains few vegetables.

The horse-riding Kazak herdsmen are traditionally clad in loose, long-sleeved furs and garments made of animal skins. The garments vary among different localities and tribes. In winter, the men usually wear sheepskin shawls, and some wear overcoats padded with camel hair, with a belt decorated with metal patterns at the waist and a sword hanging at the right side. The trousers are mostly made of sheepskin. Women wear red dresses and in winter they don cotton-padded coats, buttoned down the front. Girls like to sport embroidered cloth leggings bedecked with silver coins and other silver ornaments, which jangle as they walk. Herdsmen in the Altay area wear square caps of baby-lamb skin or fox skin covered with bright-colored brocade, while those in Ili sport round animal-skin caps. Girls used to decorate their flower-patterned hats with owl feathers, which waved in the breeze. All the women wear white-cloth shawls, embroidered with red-and-yellow designs.

Kirgiz (Chinese: 柯尔克孜族; Pinyin: Kēěrkèzī Zú)

The Kirgiz (also Kyrgyz) ethnic minority, with a population of 143,500, finds 80 per cent of its inhabitants in the Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture in the southwestern part of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The rest live in the neighboring Wushi (Uqturpan), Aksu, Shache (Yarkant), Yingisar, Taxkorgan and Pishan (Guma), and in Tekes, Zhaosu (Monggolkure), Emin (Dorbiljin), Bole (Bortala), Jinghe (Jing) and Gonliu in northern Xinjiang. Several hundred Kirgiz whose forefathers emigrated to Northeast China more than 200 years ago now live in Wujiazi Village in Fuyu County, Heilongjiang Province.

The Kirgiz language belongs to the Turkic subdivision of the Altaic family of languages. It borrowed many words from the Chinese language after the 1950s, and a new alphabet was then devised, discarding the old Arabic script and adopting a Roman alphabet-based script. The Uygur and Kazak languages are also used by the Kirgiz in some localities.

The forefathers of the Kirgiz lived on the upper reaches of the Yenisey River. In the mid-sixth century CE, the Kirgiz tribe was under the rule of the Turkic Khanate. After the Tang Dynasty (618- 907) defeated the Eastern Turkic Khanate, the Kirgiz came into contact with the dynasty and in the 7th century the Kirgiz land was officially included in China's territory.

From the 7th to the 10th century, the Kirgiz had very frequent communications with the Han Chinese. Their musical instruments -- the drum, sheng (a reed pipe), bili (a bamboo instrument with a reed mouthpiece) and panling (a group of bells attached to a tambourine) -- showed that the Kirgiz had attained quite a high level of culture. According to ancient Yenisey inscriptions on stone tablets, after the Kirgiz developed a class society, there was a sharp polarization and class antagonism. Garments, food and housing showed marked differences in wealth and there were already words for "property," "occupant," "owner" and "slave."

During the Liao and Song dynasties (916- 1279), the Kirgiz were recorded as "Xiajias" or "Xiajiaz". The Liao government established an office in the Xiajias area. In the late 12th century when Genghis Khan rose, Xiajias was recorded in Han books of history as "Qirjis" or "Jilijis," still living in the Yenisey River valley. From the Yuan Dynasty (1206- 1368) to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Jilijis, though still mainly living by nomadic animal husbandry, had emigrated from the upper Yenisey to the Tianshan Mountains and become one of the most populous Turkic-speaking tribal groups. After the 15th century, though there were still tribal distinctions, the Jilijis tribes in the Tianshan Mountains had become a unified entity.

In the early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), the Kirgiz, who had remained in the upper Yenisey River reaches, emigrated to the Tianshan Mountains to live together with their kinfolk. Many then moved to the Hindukush and Karakorum Mountains. At this time, some Kirgiz left their homeland and emigrated to Northeast China. In 1758 and 1759, the Sayak and Sarbagex tribes of Eastern Blut and the Edegena tribe of Western Blut, and 13 other tribes- a total of 200,000- entered the Issyk Kul pastoral area and asked to be subjected to the Qing.

The Kirgiz played a major role with their courage, bravery and patriotism in the defense of modern China against foreign aggression.

The Kirgiz and Kazaks assisted the Qing government in its efforts to crush the rebellion by the nobility of Dzungaria and the Senior and Junior Khawaja.

They resisted assaults by the rebellious Yukub Beg in 1864, and when the Qing troops came to southern Xinjiang to fight Yukub Beg's army, they gave them assistance.

Korean (Chinese: 朝鲜族; Pinyin: Cháoxiǎn Zú)

The largest concentration of Koreans is in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in eastern Jilin Province. Under its jurisdiction are the cities of Yanji and Tumen, and the counties of Yanji, Helong, Antu, Huichun, Wangqing and Dunhua, covering a total area of 41,500 sq. km.

The Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture is a beautiful, majestic land of high mountains and deep valleys. The land rises to 2,744 meters above sea level to the highest peak of the Changbai Mountains -- White Head Summit. This is an extinct volcano, from the crater lake of which spring the Yalu and Tumen rivers, flowing south and north respectively, and forming the boundary with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea to the east.

The area is accessible nowadays by both road and rail, except for the mountain-locked Hunchun District. The prefecture has 1,600 km of railways and 3,700 km of highways and branch roads.

Another community of Koreans lives in the Changbai Korean Autonomous County in southeastern Jilin.

The area is one of China's major sources of timber and forest products, including ginseng, marten pelts and deer antlers. It is also a habitat for many wild animals, including tigers.

Copper, lead, zinc and gold have been mined here since the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and the area also has deposits of iron, antimony, phosphorus, graphite, quartz, limestone and oil shale.

Yanbian is also blessed with agricultural riches and is a major tobacco producer. It is famous for apples and pears, which have been exported since 1955.

The ancestors of the Korean ethnic group migrated from the Korean peninsula from about the late 17th century, mostly peasants fleeing from their oppressive feudal landlords. Especially following a severe famine in the northern part of Korea in 1869, they settled down in large numbers in what is now the Yanbian area. Another wave of migration took place in the early years of this century when Japan annexed Korea and drove many peasants off the land. The Japanese seizure of the Manchurian provinces further served to drive landless Koreans to settle in Northeast China.

The Koreans have their own spoken and written language, which is thought to belong to the Altaic family. Their alphabet is a simple, ingenious one, and the Koreans are very proud of it.

Lahu (Chinese: 拉祜族; Pinyin: Lāhù Zú)

The Lahu ethnic minority has a population of 411,500, mainly distributed in the Lancang Lahu Autonomous County in Simao Prefecture, Southern Lincang Prefecture and Menghai County in western Xishuangbanna in Yunnan Province. Others live in counties along the Lancang River.

The subtropical hilly areas along the Lancang River where the Lahu people live in compact communities are fertile, suitable for planting rice paddy, dry rice, maize, buckwheat as well as tea, tobacco, and sisal hemp. There are China fir and pine, camphor and nanmu trees in the dense forests, which are the habitat of such animals as red deer, muntjacs, wild oxen, bears, peacocks and parrots. Found here are also valuable medicinal herbs like pseudo-ginseng and devil pepper.

Mineral resources in the area include iron, copper, lead, aluminum, coal, silver, mica and tungsten.

The Lahu language belongs to the Chinese-Tibetan language family. Most of the Lahus also speak Chinese and the language of the Dais. In the past the custom of passing messages by wood-carving was prevalent. In some parts the alphabetic script invented by Western priests was in use. After liberation, the script was reformed and became their formal written language.

Legend says that the forbears of the Lahu people, who were hunters, began migrating southward to lush grassland which they discovered while pursuing a red deer.

Some scholars hold that during the Western Han Dynasty more than 2,000 years ago, the "Kunmings," the nomadic tribe pasturing in the Erhai area in western Yunnan, might be the forbears of certain ethnic groups, including the Lahus. Then, the "Kunming" people still lived in a primitive society "without common rulers." They belonged to different clans engaged in hunting. The Lahu people once were known for their skill at hunting tigers. They roved over the lush slopes of the towering Ailao and Wuliang mountains.

In the 8th century, after the rise of the Nanzhao regime in Yunnan, the Lahu people were compelled to move south. By no later than the beginning of the 18th century they already had settled in their present-day places. Influenced by the feudal production methods of neighboring Han and Dai peoples, they turned to agriculture. With economic development, they gradually passed into a feudal system, and their life style and customs were more or less influenced by the Hans and Dais.

Lhoba (Chinese: 珞巴族; Pinyin: Luòbā Zú)

The 2,300 people of the Lhoba ethnic minority have their homes mainly in Mainling, Medog, Lhunze and Nangxian counties in southeastern Tibet. Additionally, a small number live in Luoyu, southern Tibet.

The Lhobas speak a distinctive language belonging to the Tibetan-Myanmese language family, Chinese-Tibetan language system. Few of them know the Tibetan language. Having no written script, Lhoba people used to keep records by notching wood or tying knots.

People of this ethnic group were oppressed, bullied and discriminated against by the Tibetan local government, manorial lords and monasteries under feudal serfdom in Tibet. Being considered inferior and "wild," some were expelled and forced to live in forests and mountains. They were not allowed to leave their areas without permission and were forbidden to do business with other ethnic groups. Intermarriage with Tibetans was banned. They had to make their living by gathering food, hunting and fishing because of low grain yields in the region.

Li (Chinese: 黎族; Pinyin: Lí Zú)

Hainan, China's only island province, is the home of the Li ethnic group with a population of about 1.11 million. Most of them live in and around Tongze, capital of the Hainan Li-Miao Autonomous Prefecture, and Baoting, Ledong, Dongfang and other counties under its jurisdiction; others live among people of the Han and Hui ethnic groups in other parts of the island.

Lying at the foot of the Wuzhi Mountains, the Li area is a tropical paradise with fertile land and abundant rainfall. Coconut palms and rubber trees line the beaches and people in some places reap three crops of rice a year and grow maize and sweet potatoes all the year round. The area is the country's major producer of tropical crops such as coconut, arica, sisal hemp, lemon grass, cocoa, coffee, rubber, oil palm, cashew, pineapple, casava, mango and banana.

The island is abundant in minerals like copper, tin, crystal quarts, phosphorus, iron and tungsten. There are numerous salt pans and many fine harbors along the coast, and good fishing grounds off the shore. Pearls, coral and hawksbill, turtles of commercial value are found in the coastal waters. Black gibbons, civets and peacocks live in the primeval forests which abound with valuable timber trees.

The Lis had no written script. Their spoken language belongs to the Chinese-Tibetan language family. But many of them now speak the Chinese language. A new Romanized script was created for the Li ethnic group in 1957 with government help.

According to historical records, the term "Li" first appeared in the Tang Dynasty (618- 907). The Lis are believed to be descendants of the ancient Yue ethnic group, with especially close relations with the Luoyues -- a branch of the Yues -- who migrated from Guangdong and Guangxi on the mainland to Hainan Island long before the Qin Dynasty (221- 206 BCE). Archaeological finds on the island show that Li ancestors settled there some 3,000 years ago during the late Shang Dynasty or early Zhou Dynasty when they led a primitive matriarchal communal life. Ethnically, the Lis are closely related to the Zhuang, Bouyei, Shui, Dong and Dai ethnic groups, and their languages bear resemblance in pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary. People of the Han ethnic group began to settle on the island also before the Qin Dynasty as farmers, fishermen and merchants. Together, people of the two ethnic groups contributed to the development of Hainan. Later, the Han Dynasty sent troops under Lu Bode and Ma Yuan to set up prefectures and strengthen government control there and enhance relations between the mainland and the island.

In the 6th century, Madame Xian, a political leader of the Yues in southwest Guangdong, Hainan and the Leizhou Peninsula, pledged allegiance to the Sui Dynasty. Her effort in promoting national unity and unification of the country not only enhanced the relationship between Hainan Island and the central part of China but also helped the development of the primitive Li society by introducing feudal elements into it.

The Tang Dynasty (618- 907) further strengthened central control over the Li areas by setting up five prefectures which consisted of 22 counties. In the Song Dynasty (960- 1279), rice cultivation was introduced and irrigation developed, and local farmers were able to grow four crops of ramie annually. Brocade woven by Li women became popular in central China.

In the early Yuan Dynasty, Huang Daopo, the legendary weaver in Chinese history, achieved her excellence by learning weaving techniques from the Lis. Running away as a child bride from her home in Shanghai, she came to Hainan and lived with the Lis there. Returning to Shanghai, she passed on the Li techniques to others and invented a cotton fluffer, a pedal spinning wheel and looms, which were the most advanced in the world at the time.

The feudal mode of production became dominant in Hainan during the Ming and Qing dynasties as elsewhere in China. Most of the land was in the hands of a small number of landlords, and peasants were exploited by usury and land rent. Large tracts of land were seized by the government for official use. Only in the Wuzhi Mountains did people still work the land collectively, but even this remnant of the communal system was used by feudal landlords as a means of exploitation.

Heavy oppression of the Li people kindled flames of uprising. In the Song and Yuan dynasties, the Lis in Hainan staged 18 large-scale uprisings; during the Ming and Qing dynasties 14 major rebellions took place. After the Opium War in 1840, Hainan was invaded by foreign imperialists who brought untold sufferings to the local Li and Han people, who rose repeatedly against the foreign invaders.

The Japanese invaded Hainan Island in February 1939. People of various nationalities in Hainan rose in resistance. In the spring of 1944, an anti- Japanese guerrilla force, the Qiongya Column, was formed. It grew into an army of 7,000 towards the end of the war, liberating three-fifths of the island.

Lisu (Chinese: 傈僳族; Pinyin: Lìsù Zú)

The Lisu ethnic group numbers 574,600 people, and most of them live in concentrated communities in Bijiang, Fugong, Gongshan and Lushui counties of the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture in northwestern Yunnan Province. The rest are scattered in Lijiang, Baoshan, Diqing, Dehong, Dali, Chuxiong prefectures or counties in Yunnan Province as well as in Xichang and Yanbian counties in Sichuan Province, living in small communities with the Han, Bai, Yi and Naxi peoples.

The Lisu language belongs to the Chinese-Tibetan language family. In 1957, a new alphabetic script was created for the Lisu people.

The Lisus inhabit a mountainous area slashed by rivers. It is flanked by Gaoligong Mountain on the west and Biluo Mountain on the east, both over 4,000 meters above sea level. The Nujiang River and the Lancang River flow through the area, forming two big valleys. The average annual temperature along the river basins ranges between 17 and 26 degrees Centigrade, and the annual rainfall averages 2,500 millimeters. Main farm crops are maize, rice, wheat, buckwheat, sorghum and beans. Cash crops include ramie, lacquer trees and sugarcane. Many parts of the mountains are covered with dense forests, famous for their China firs. In addition to rare animals, the forests yield many medicinal herbs including the rhizome of Chinese gold thread and the bulb of fritillary. The Lisu area also has abundant mineral and water resources.

According to historical records and folk legend, the forbears of the Lisu people lived along the banks of the Jinsha River and were once ruled by "Wudeng" and "Lianglin," two powerful tribes. After the 12th century, the Lisu people came under the rule of the Lijiang Prefectural Administration of the Yuan Dynasty, and in the succeeding Ming Dynasty, under the rule of the Lijiang district magistrate with the family surname of Mu.

During the 1820s, the Qing government sent officials to Lijiang, Yongsheng and Huaping, areas where the Lisus lived in compact communities, to replace Naxi and Bai hereditary chieftains. This practice speeded up the transformation of the feudal manorial economy to a landlord economy, and tightened up the rule of the Qing court over Lisu and other ethnic groups. In the years preceding and following the turn of the 20th century, large numbers of Han, Bai and Naxi peoples moved to the Nujiang River valleys, taking with them iron farm tools and more advanced production techniques, giving an impetus to local production.

For a long time the Lisus, under oppression and exploitation by landlords, chieftains and headmen, as well as the Kuomintang and foreign imperialists, led a miserable life. In Eduoluo Village of Bijiang County alone, 237 peasants out of the village's 1,000 population were tortured to death in the 10 years prior to liberation by local officials, chieftains, headmen or landlords. The Lisus also suffered exorbitant taxes and levies. The household tax, for example, was 21 kilograms of maize per capita, accounting for 21 per cent of the annual grain harvest. Moreover, there were unscrupulous merchants and usurers. The arrival of imperialist influence at the turn of the 20th century put the Lisus in a far worse plight.

During the period between the 18th and 19th century, the Lisus waged many struggles against oppression. From 1941 to 1943, together with the Hans, Dais and Jingpos, they heroically resisted the Japanese troops invading western Yunnan Province and succeeded in preventing the aggressors from crossing the Nujiang River, contributing to the defense of China's frontier.

Manchu (Chinese: 满族; Pinyin: Mǎn Zú)

Like the Han people, the majority ethnic group in China, over 70 per cent of the Manchus are engaged in agriculture-related jobs. Their main crops include soybean, sorghum, corn, millet, tobacco and apple. They also raise tussah silkworms. For Manchus living in remote mountainous areas, gathering ginseng, mushroom and edible fungus makes an important sideline. Most of the Manchu people in cities, who are better educated, are engaged in traditional and modern industries.

Manchus have their own script and language, which belongs to the Manchu-Tungusic group of the Altaic language family. Beginning from the 1640s, large numbers of Manchus moved to south of the Shanhaiguan Pass (east end of the Great Wall), and gradually adopted Mandarin Chinese as their spoken language. Later, as more and more Han people moved to north of the pass, many local Manchus picked up Mandarin Chinese too.

An ethnic group originally living in forests and mountains in northeast China, the Manchus excelled in archery and horsemanship. Children were taught the art of swan-hunting with wooden bows and arrows at six or seven, and teenagers learned to ride on horseback in full hunting gear, racing through forests and mountains. Women, as well as men, were skilled equestrians.

The ancestry of the Manchus can be traced back more than 2,000 years to the Sushen tribe, and later to the Yilou, Huji, Mohe and Nuzhen tribes native to the Changbai Mountains and the drainage area of the Heilong River in northeast China.

As testified to by the stone arrowheads and pomegranate-wood bows they sent as tributes to rulers of the Western and Eastern Zhou period (11th century- 221 BCE), the Sushens were one of the earliest tribes living along the reaches of the Heilong and Wusuli rivers north of the Changbai Mountains.

After the Warring States Period (475- 221 BCE), the Sushens changed the name of their tribe to Yilou. They ranged over an extensive area covering the present-day northern Liaoning Province, the whole of Jilin Province, the eastern half of Heilongjiang Province, east of the Wusuli River, and north of the Heilong River. Stone arrowheads and pomegranate-wood bows still distinguished the Yilous in hunting wild boar. They also mastered such skills as raising hogs, growing grain, weaving linen and making small boats. They pledged allegiance to dynastic rulers on the Central Plains after the Three Kingdoms period (220- 280).

During the period between the 4th and 7th centuries, descendants of the Yilous called themselves Hujis and Mohes, consisting of several dozen tribes.

By the end of the 7th century a local power called the State of Zhen with the Mohes of the Sumo tribe as the majority was formed under the leadership of Da Zuorong on the upper reaches of the Songhua River north of the Changbai Mountains. In 713, the Tang court conferred on Da Zuorong the title of "King of Bohai Prefecture" and made him "Military Governor of Huhan Prefecture." Da's domain, known afterwards as the State of Bohai, showed marvelous skills in iron smelting and silk weaving. With its political and military institutions modeled on those of the Tang Dynasty (618- 907), this society adopted the Han script. Under the influence of the political and economic systems of the central part of China and the more developed science and culture there, speedy advances were made in agriculture and handicraft industries.

Then the Liao Dynasty (916- 1125) conquered the State of Bohai and moved the Bohai tribesmen southward. Along with this movement, the Mohes in the Heilong River valley made a southward expansion. Gradually a people known as Nuzhens built a powerful state in the former domain of Bohai.

The early 12th century saw a successful insurrection led by Aguoda with the Wanyan tribe of the Nuzhen people as a key force in their fight against the Liao Dynasty, founding the regime of Kin (1115- 1234). After the termination of the Liao, the Kin armies destroyed the Northern Song (960- 1126) and rose as a power in opposition to the rule of the Southern Song (1127- 1279). Moving to live en masse on the Central Plains, the Nuzhens gradually became assimilated with the Han people.

Early in the 13th century, the Nuzhens were conquered by the Mongols and later came under the rule of the Yuan Dynasty (1271- 1368). With the largest concentration in Yilan, Heilongjiang Province, they settled on the middle and lower reaches of the Heilong River and along the Songhua and Wusuli rivers, extending to the sea in the east. The Yuan Dynasty enlisted the service of local upper-strata residents to create five administrations each governing 10,000 house-holds, known respectively as Taowen, Huligai, Woduolian, Tuowolian and Bokujiang. The Nuzhens at this time were still leading a primitive life. They developed and progressed, until Nurhachi's son proclaimed the name of Manchu towards the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368- 1644).

The Ming Dynasty had 384 military forts and outposts established in the Nuzhen area, and the Nuergan Garrison Command, a local military and administrative organization in Telin area opposite the confluence of the Heilong and Henggun rivers, was placed directly under the Ming court. While strengthening central government control over northeast China, these establishments aided the economic and cultural exchanges between the Nuzhen and Han peoples.

From the mid-16th century onwards, repeated internecine wars broke out among the Nuzhens, but they were later reunified by Nurhachi, who was then Governor of Jianzhou Prefecture.

In 1595, the Ming court conferred on Nurhachi the title of "Dragon-Tiger General" after making him a garrison commander in 1583 and public procurator of Heilongjiang Province in 1589. Frequent trips to Beijing brought him full awareness of developments in the Han areas, which in turn exerted great influence on him. A talented political and military leader, he later proved his outstanding ability by welding together within 30 years all the Nuzhen tribes that were scattered over a vast area reaching as far as the sea in the east, Kaiyuan in the west, the Nenjiang River in the north and the Yalu River in the south.

Once the Nuzhens were united, Nurhachi initiated the "Eight banner" system, under which all people were organized along military lines. Each banner consisted of many basic units called "niulu" which functioned as the primary political, military and production organization of the Manchu people, and each unit was formed of 300 people. Members of these units hunted or farmed together in peace time, and in time of war all would go into battle as militia.

In 1619 Nurhachi proclaimed himself "Sagacious Khan" and established a slave state known to later times as Late Kin.

Maonan (Chinese: 毛南族; Pinyin: Màonán Zú)

The Maonan ethnic minority has a population of 72,400, living in the northern part of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

The Maonan communities are located in sub-tropical areas characterized by a mild climate and beautiful scenery, with stony hills jutting up here and there, among which small patches of flatland are scattered. There are many small streams which are used to irrigate paddy rice fields. Drought-resistant crops are grown in the Dashi Mountain area where water is scarce. In addition to paddy rice, agricultural crops include maize, wheat, Chinese sorghum, sweet potatoes, soybean, cotton and tobacco. Special local products include camphor, palm fiber and musk. The area abounds in mineral resources such as iron, manganese, stibium and mercury. The Maonans are experts in raising beef cattle, which are marketed in Shanghai, Guangzhou and Hong Kong.

People surnamed Tan take up 80 per cent of the population. Legend has it that their ancestors earlier lived in Hunan Province, then emigrated to Guangxi and multiplied by marrying the local women who spoke the Maonan tongue. There are other Maonans surnamed Lu, Meng, Wei and Yan, whose ancestral homes are said to have been in Shandong and Fujian provinces.

The Maonan language belongs to the Dong-Shui branch of the Zhuang-Dong language group of the Chinese-Tibetan language family. Almost all the Maonans know both the Han and the Zhuang languages because of long contact with those people.

Long subjected to the oppression of the ruling class, the Maonan areas developed very slowly. At the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368- 1644), the Maonans still used wooden hoes and ploughs. Various iron tools were in use by the time of Qing Dynasty (1644- 1911), when land was gradually concentrated and the division of classes became distinct. There began to appear farm laborers who did not own an inch of land, poor peasants who had a small amount of land, self-sufficient middle peasants, and landlords and rich peasants who owned large amounts. The landlords and rich peasants cruelly exploited farm laborers and poor peasants by means of land rent and usury. There were also slave girls either bought by the landlords or forced by unpaid debts to serve landlords all their lives.

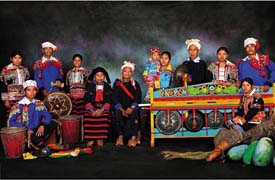

Miao (Chinese: 苗族; Pinyin: Miáo Zú)

With a population of more than seven million, the Miao people form one of the largest ethnic minorities in southwest China. They are mainly distributed across Guizhou, Yunnan, Hunan and Sichuan provinces and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and a small number live on Hainan Island in Guangdong Province and in southwest Hubei Province. Most of them live in tightly-knit communities, with a few living in areas inhabited by several other ethnic groups.

On the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau and in some remote mountainous areas, Miao villages are comprised of a few families, and are scattered on mountain slopes and plains with easy access to transport links.

Much of the Miao area is hilly or mountainous, and is drained by several big rivers. The weather is mild with a generous rainfall, and the area is rich in natural resources. Major crops include paddy rice, maize, potatoes, Chinese sorghum, beans, rape, peanuts, tobacco, ramie, sugar cane, cotton, oil-tea camellia and tung tree. Hainan Island is abundant in tropical fruits.

As early as the Qin and Han dynasties 2,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Miao people lived in the western part of present-day Hunan and the eastern part of present-day Guizhou. They were referred to as the Miaos in Chinese documents of the Tang and Song period (618- 1279).

In the third century CE, the ancestors of the Miaos went west to present-day northwest Guizhou and south Sichuan along the Wujiang River. In the fifth century, some Miao groups moved to east Sichuan and west Guizhou. In the ninth century, some were taken to Yunnan as captives. In the 16th century, some Miaos settled on Hainan Island. As a result of these large-scale migrations over many centuries the Miaos became widely dispersed.

Such a wide distribution and the influence of different environments has resulted in marked differences in dialect, names and clothes. Some Miao people from different areas have great difficulty in communicating with each other. Their art and festivals also differ between areas.

The Miao language belongs to the Miao-Yao branch of the Chinese-Tibetan language family. It has three main dialects in China -- one based in west Hunan, one in east Guizhou and the other in Sichuan, Yunnan and part of Guizhou. In some places, people who call themselves Miao use the languages of other ethnic groups. In Chengbu and Suining in Hunan, Longsheng and Ziyuan in Guangxi and Jinping in Guizhou, about 100,000 Miao people speak a Chinese dialect. In Sangjiang in Guangxi, over 30,000 Miaos speak the Dong language, and on Hainan Island, more than 100,000 people speak the language of the Yaos. Due to their centuries of contacts with the Hans, many Miaos can also speak Chinese.

Monba (Chinese: 门巴族; Pinyin: Ménbā Zú)

The Moinbas are scattered in the southern part of Tibet Autonomous Region. Most of them live in Medog, Nyingch and Cona counties.

They have forged close links with the Tibetan people through political, economic and cultural exchanges and intermarriage over the years. They share with the Tibetans the common belief in Lamaism and have similar customs and lifestyles.

Their language, which has many dialects, belongs to the Tibetan-Myanmese language family, and many of them can speak Tibetan.

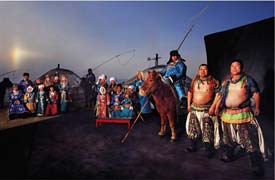

Mongol (Chinese: 蒙古族; Pinyin: Měnggǔ Zú)

The Mongolians live mostly in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, with the rest residing in Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Hebei, Henan, Sichuan, Yunnan and Beijing. /Having their own spoken and written language, which belongs to the Mongolian group of the Altaic language family, the Mongolians use three dialects: Inner Mongolian, Barag-Buryat and Uirad. The Mongolian script was created in the early 13th century on the basis of the script of Huihu or ancient Uygur, which was revised and developed a century later into the form used to this day.

The largest Mongolian area, the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region with its capital at Hohhot, was founded on May 1, 1947, as the earliest such establishment in China. This vast and rich expanse of land is inhabited by 21,780,000 people, of whom about 2 million are Mongolians and the rest Hans, Huis, Manchus, Daurs, Ewenkis, Oroqens and Koreans.

The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region is located in the northern part of China. Covering 1.2 million square kilometers and rising 900 to 1,300 meters above sea level, it has vast tracts of excellent natural pastureland with numerous herds of cattle, sheep, horses and camels. The Yellow River Bend and Tumochuan plains, known as a "Granary North of the Great Wall," are crisscrossed with streams and canals. Over southwestern Inner Mongolia flows the Yellow River, which is, among other things, famous for its carp and the well-developed irrigation and transport facilities it has provided for the area. Inner Mongolia also has several hundred richly endowed salt and alkali lakes and many large freshwater lakes, including Hulun Nur, Buir Nur, Ulansu Nur, Dai Hai and Huangqi Hai. More than 60 mineral resources such as coal, iron, chromium, manganese, copper, lead, zinc, gold, silver, tin, mica, graphite, rock crystal and asbestos have been found. The Greater Hinggan Mountain Range in the east part of the region boasts China's largest forests, which are also a fine habitat for a good many rare species of wildlife. This unique natural environment makes the region a famous producer of precious hides, pilose antler, bear gallbladder, musk, Chinese caterpillar fungus (Cordyceps sinensis), as well as 400 varieties of Chinese medicinal herbs, including licorice root, "dangshen" (Codonopsis pilosula), Chinese ephedra (Ephedra sinica), and the root of membranous milk vetch (Astragalus membranaceus). Specialities of the region known far and wide are mushrooms and day lily flowers, which enjoy brisk sales on both the domestic and world markets.

Following the founding of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, autonomous prefectures and counties were established in other provinces where Mongolians live in large communities. These include the two Mongolian autonomous prefectures of Boertala and Bayinguoleng in Xinjiang, the Mongolian and Kazak Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai, and the seven autonomous counties in Xinjiang, Qinghai, Gansu, Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning. Enjoying the same rights as all other nationalities in China, the Mongolians are joining them in running the country as its true masters.

Mongol was initially the name of a tribe roaming along the Erguna River. Moving to the grasslands of western Mongolia in the 7th century, the Mongols settled in the upper reaches of the Onon, Kerulen and Tula rivers and areas east of the Kentey Mountains in the 12th century. Later, their offshoots grew into many tribal groups, such as Qiyan, Zadalan and Taichiwu. The Mongolian grasslands and the forests around Lake Baikal were also home to many other tribes such as Tartar, Wongjiqa, Mierqi, Woyela, Kelie, Naiman and Wanggu, which varied in size and economic and cultural development.

Early in the 13th century, Temujin of the Mongol tribe unified all these tribes to form a new national community called Mongol. In 1206, he had a clan conference held on the bank of the Onon River, at which he was elected the Great Khan of all Mongols with the title of Genghis Khan. This was followed by the founding of a centralized feudal khanate under aristocratic rule, which promoted the development of Mongolian society. Military conquests ensued on a large scale soon after Temujin's accession to the throne. In 1211 and 1215, he launched massive attacks against the State of Kin (1115- 1234) and captured Zhongdu (present-day Beijing). In 1219 he began his first Western expedition, extending his jurisdiction as far as Central Asia and southern Russia. He died in 1227.

In 1260, Kublai Khan (1215- 1294) became the Great Khan and moved his capital from Helin north of the Gobi Desert to Yanjing, which was later renamed Dadu (Great Capital). In 1272 he founded the Yuan Dynasty (1206- 1368), and in 1279 he subdued the Southern Song (1127- 1279), bringing the whole of China under his centralized rule.

The subsequent Ming Dynasty (1368- 1644) placed the areas where Mongols lived under the administration of more than 20 garrison posts commanded by Mongolian manorial lords. In the early 15th century the Wala (Woyela) and Tartar Mongols living west and north of the Gobi Desert pledged their allegiance to the Ming empire.

In the Qing Dynasty (1644- 1911) more Mongol feudal lords dispatched emissaries to Beijing and presented tributes to the Qing court. Later, some Jungar feudal lords of the Elutes, incited by Tsarist Russia, staged rebellions against the central government. They were put down by the Qing court through repeated punitive expeditions and the Mongolian areas were reunified under the central authorities.

To tighten its control over the various Mongol tribes, the Qing government instituted in Mongolia a system of leagues and banners on the basis of the Manchu Eight-Banner Institution.

The Mongolians have a fine cultural tradition, and they have made indelible contributions to China in culture and science. They created their script in the 13th century and later produced many outstanding historical and literary works, including the Inside History of Mongolia of the Mid-13th Century and the History of the Song Dynasty, History of the Liao Dynasty and History of the Kin Dynasty edited by Tuo Tuo, a Mongolian historian during the Yuan Dynasty. The reign also enjoyed a galaxy of Mongolian calligraphers and authors like Quji Wosier who was credited with many works and translations done in the Han and Tibetan languages. Da Yuan Yi Tong Zhi (China's Unification under the Great Yuan Dynasty) was a famous work of geographical studies compiled under the auspices of the Yuan court. Mongolian architecture in the construction of cities and especially of palaces at that time was also unique.

Further advances in culture were made by Mongolians in the Ming Dynasty. Apart from such great literary and historical works as the Golden History of Mongolia, An Outline of the Golden History of Mongolia and Stories of Heir Apparent Wubashehong, Mongolian scholars produced many grammar books and dictionaries, as well as translations of the Inside History of Mongolia and the Buddhist Scripture Kanjur done into Chinese. These works enriched Mongolian culture and promoted cultural exchanges between the Mongolian, Han and Tibetan people.

The development of Mongolian culture in the subsequent Qing Dynasty was represented by a greater number of dictionaries and reference books like the Principles of Mongolian, A Collection of Mongolian Words and Phrases, Exegesis of Mongolian Words, Mongolian-Tuote Dictionary, Mongolian-Tibetan Dictionary, Manchurian-Mongolian-Han-Tibetan Dictionary, Manchurian-Mongolian-Han-Tibetan-Uygur Dictionary, Manchurian-Mongolian-Han Tibetan-Uygur-Tuote Dictionary and A Concise Dictionary of Manchurian, Mongolian and Han. Noted literary and historical works included The Origin and Growth of Mongolia, Peace and Prosperity Under the Great Yuan Dynasty, Random Notes from the West Studio, Miscellanies from Fengcheng, A Guide to a Means of Life, A One-storied House, and Weeping Scarlet Pavilion. Mongolian scholars also translated such Chinese classics as A Dream of Red Mansions, Outlaws of the Marsh, Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Pilgrimage of the West.

The Stories of Shageder, also produced in this period, has been regarded as the most outstanding work in the treasure-house of Mongolian literature. Other great works of folk literature include the Story of Gessar Khan of the 11th century, the Life Story of Jianggar, an epic of the 15th century.

Mongolians owed their achievements in medical science, astronomy and calendar to the influence of the Hans and Tibetans. Mongolian medicine has been best known for its Lamaist therapy, which is most effective for traumatic surgery and the setting of fractured bones. To further develop their medical science, the Mongolians have translated into Mongolian many Han and Tibetan medical works, which include Mongolian-Tibetan Medicine, A Compendium of Medical Science, The of Secret of Pulse Taking, Basic Theories on Medical Science in Four Volumes, Pharmaceutics and Five Canons of Pharmacology. Outstanding contributions have also been made by the Mongolians in the veterinary science. In the field of mathematics and calendar, credit should be given to the Mongolian astronomist and mathematician Ming Antu. During the decades of his service in the Imperial Observatory, he participated in compiling and editing the Origin and Development of Calendar, Sequel to a Study of Universal Phenomena and A Study of the Armillary Sphere. His work Quick Method for Determining Segment Areas and Evaluation of the Ratio of the Circumference of a Circle to Its Diameter (completed by his son and students) is also a contribution to China's development in mathematics. He also made a name for himself in cartography. It was due to his geographical surveys in Xinjiang that the Complete Atlas of the Empire, the first atlas of China drawn with scientific methods, was finished.

Mosuo (Chinese: 摩梭; Pinyin: Mósuō)

The Mosuo are a small ethnic group living in Yunnan and Sichuan Provinces in China, close to the border with Tibet. Consisting of a population of 50,000, most of them are found near Lugu Lake, high in the Tibetan Himalayas 27°42′35.30″N, 100°47′4.05″E. Although culturally distinct from the Naxi, the Chinese government places them as members of the Naxi minority.

Mulam (Chinese: 仫佬族; Pinyin: Mùlǎo Zú)

The Mulam ethnic minority has a population of 160,600, of which the majority live in Luocheng County in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Others are scattered in neighboring counties.

The Mulam language is a member of the Zhuang-Dong language group of the Chinese-Tibetan language family, but because of extensive contacts with the majority Han and local Zhuangs many Mulams speak one or both of these languages in addition to their own.