"By means of an ingenious transfer from a linen I acquired in Constantinople," replied the knight. Charny retained the linen, using it for more parties. An admiring public called it miraculous and eventually dubbed it the shroud of Turin.

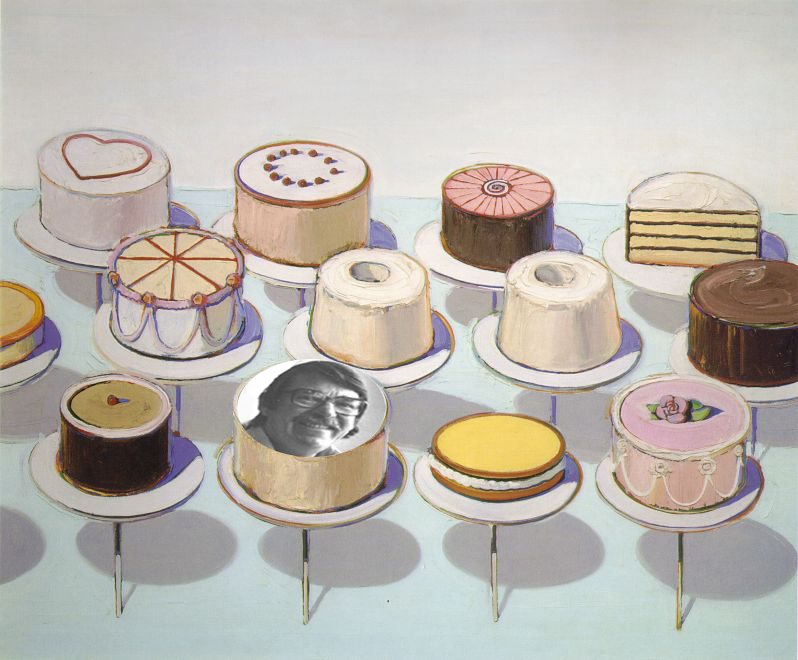

Since that time, face cakes played an important role in the commingling of cookery and art history. Famous artists including Velazquez and Rembrandt were commissioned to paint face cakes for patrons. In light of his work as a cake painter, controversy has arisen concerning Velazquez's Las Meninas. The painting shows Velazquez as he paints the King and Queen, who appear reflected in a hanging mirror. A small but vocal minority of art historians argues that the while painting cakes, Velazquez used this mirror to project the royals' likeness onto a canvas of edible rabbit hide. Modern artists have continued the face cake tradition. As seen in this early study, Wayne Thiebaud originally planned to include a picture of Richard Diebenkorn in the front row of his 1963 painting cakes. Face cake is not only a domain of artists, but also of adventurers. In 1872 Sir Francis Galton published his famous book The Art of Travel, in which he describes, among other important skills, the management of savages. A section of Galton's book titled "Seizing Food" reads:

Face cake is not only a domain of artists, but also of adventurers. In 1872 Sir Francis Galton published his famous book The Art of Travel, in which he describes, among other important skills, the management of savages. A section of Galton's book titled "Seizing Food" reads:

On arriving at an encampment, the natives commonly run away in fright. If you are hungry, or in serious need of anything that they have, go boldly into their huts, take just what you want, and leave fully adequate payment. It is absurd to be over-scrupulous in these cases.But even for Galton, things didn't always run according to plan. Galton's unpublished diary notes that savages show special attachment to certain foods:

We set upon the encampment during a feast day. Despite our shouts and threats of violence, however, the native horde stood fast, pelting us with stones. Only after great battle did they quit the table, where we found the reason for the savages' tenacity: a dough baked in the likeness of a man and adorned with flaming tallow.On his return to London, Galton thrilled influential friends by presenting them with baked portraits of themselves. Like so many technologies, face cakes leapt forward in sophistication during the years surrounding World War II. To combat daily stresses, scientists of the Manhattan Project blew off steam at raucous birthday parties. Before they became more careful with radiation, Los Alamos scientists often embellished face cakes with fissile material to make them glow. In 1944 a chemist named Don Mastick ingested several milligrams of plutonium, the glowing eyes in a birthday cake for J. Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer forbade future radioactive cakes, but he did admit that the plutonium eyes were "creepy." Face cakes reached their technical zenith in 1945 when Ansel Adams threw a birthday party for Alfred Steiglitz at Georgia O'Keefe's ranch at Abiquiu, New Mexico. Adams used a solar emulsifying agent laid atop a gelatin base to capture a portrait of Steiglitz in a moment of quiet reflection. Steiglitz, who spent his career arguing for the validity of photography as an art form, was moved to say, "I don't care what the cake tastes like; it's me! Look at that, Georgia!" The advent of computer imaging has elevated face cake realism. But with this technology has come controversy. A 1998 court case brought face cakes to the fore of American jurisprudence. The case, Wylder vs. Jones, focused on a cake commissioned for an office party at Tri-County Lunch Solutions of Greeley, Colorado. The cake showed the plaintiff, Debra Wylder's face, electronically superimposed on a photo of Monica Lewinksy, standing beside a priapic Bill Clinton. The case gave Congress impetus to pass the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which forbids merchants from selling seditious face cakes, even if the purchaser was just kidding. With such a history behind the practice, I'm excited to bake my father's face onto a cake. These days even a home baker can make a face cake. But should a rank amateur be concerned about his skill as an artist? Absolutely not says the website photofrost.com. "It's a whole new art form, yet it's easy,"photoFrost's editors assure me. But what about quality; should I worry about flavor? Again, no, since photoFrost icings "DON'T have a strange texture or taste.... They DON'T add an extra layer or 'skin' to your cake." That's exactly what's I'm looking for. My dad will be so happy.