‘A few miles away from College Station (ie the Texas A&M College, where Lomax first began collecting folk songs) runs the Brazos River. The broad bottom lands of that river were covered with large cotton plantations. There, one day in 1908, behind lowered curtains in the home of a bachelor overseer I first saw jazz danced between the sexes. Even this rough man was unwilling to allow the public to know that he permitted young Negroes to dance in the postures now accepted as a matter of course in barrel-houses and honkytonks in cities of the South. I discovered at this time the Ballet Of The Boll Weevil, Dink’s Fare You Well, Oh Honey and many ‘blues’. Carl Sandburg, whom I place first among all present amateur folk singers, uses regularly the first two songs on his programmes. He says that Dink’s song reminds him of Sappho.

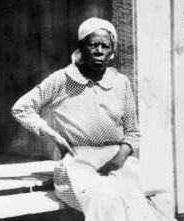

I found Dink washing her man’s clothes outside their tent on the bank of the Brazos River in Texas. Many other similar tents stood around. The black men and women they sheltered belonged to a levee-building outfit from the Mississippi River Delta, the women having been shipped from Memphis along with the mules and the iron scrapers, while the men, all skilful levee-builders, came from Vicksburg. A white foreman volunteered: ‘Without women of their own, these levee Negroes would have been all over the bottoms every night hunting for women. That would mean trouble, serious trouble. Negroes can’t work when sliced up with razors.’

The two groups of men and women had never seen each other until they met on the river bank in Texas where the white levee contractor gave them the opportunity presented to Adam and Eve – they were left alone to mate after looking each other over. While her man built the levee, each woman kept his tent, toted the water, cut the firewood, cooked, washed his clothes and warmed his bed. Down on the dumps nearer the river, clouds of drifting dust swirled from the feet of moving mules and from piles of shifted earth, while the shouts of the muleskinners sometimes grouped themselves into long-drawn-out couplets with a semi-tune – levee camp hollers:

I looked all over the corral,

Lawd, I couldn’t find a mule with his shoulder well.

Lawd, they won’t ‘low me to beat ’em,

Got to beg ’em along.

But Dink, reputedly the best singer in the camp, would give me no songs. ‘Today ain’t my singin’ day,’ she would reply to my urging. Finally, a bottle of gin, bought at a nearby plantation commissary, loosed her muse. The bottle of liquor soon disappeared. She sang, as she scrubbed her man’s dirty clothes, the pathetic story of a woman deserted by her lover when she needs him most – a very old story. Dink ended the refrain with a subdued cry of despair and longing – the sobbing of a woman deserted by her man.

If I had wings like Norah’s dove

C#m A

I’d fly up the river to the one I love

E A E B7 E

Fare thee well, oh my honey, fare thee well

I’ve got a man, he’s long and tall

Moves his body like a cannon ball

Fare thee well, oh my honey, fare thee well

One of these days and it won’t be long

Call my name and I’ll be gone

Fare thee well, oh my honey, fare thee well

I remember one night, a drizzling rain

Round my heart I felt a pain

Fare thee well, oh my honey, fare thee well

If I had listened to what my mama said

I’d be at home in my mama’s bed

Fare thee well, oh my honey, fare thee well

(c) 2000 McGuinn Music / Roger McGuinn